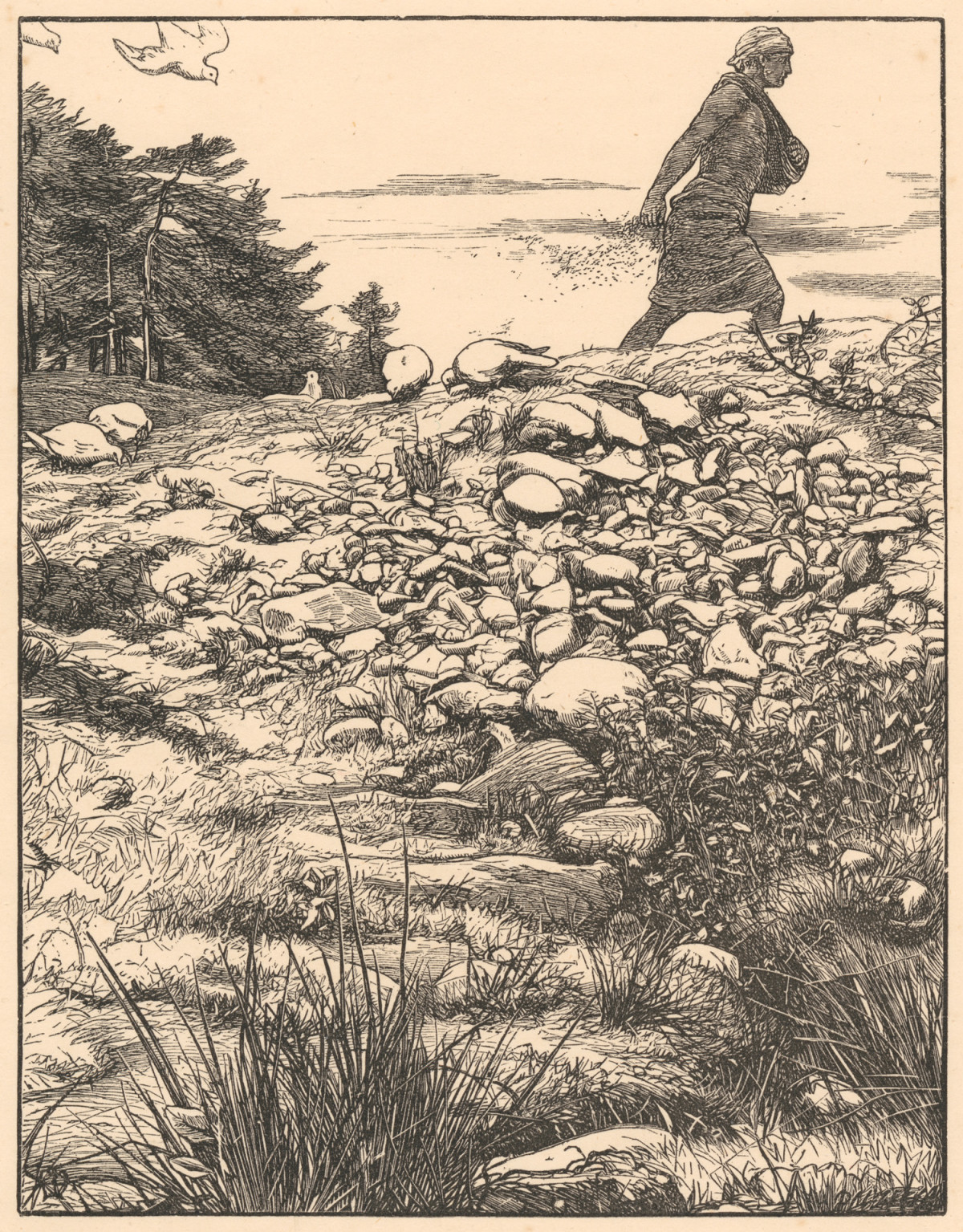

Sir John Everett Millais wood engraving, The Parable of the Sower,

produced in 1863 for Good Words.

Alongside the advancements in printing technology that allowed the Victorian print market to flourish, there were simultaneous strides being made in the world of illustration. New technologies in engraving introduced a new era of illustrated fiction. From its start in the 1820s as a marketing technique for booksellers, the demand for illustrated fiction continued to grow, reaching its height in the 1860s and leading to the ubiquitous presence of images in magazines, newspapers, and novels.1

Thus, Victorian novel reading became inherently visual. The “surge of illustrated material transformed Victorian print culture and reading practices as illustration became central to both.”2 This pervasiveness of visual material is none more starkly depicted than in the installment novel. And, as this form was the most common method through which Victorian readers approached many novels for the first time, visuality became fundamental to their understanding of the work itself. But, even for those who encountered illustrated copies secondarily to a first reading, the prevalence of illustration and Victorian readers' familiarity with it would have ensured they took notice of them. The popularity of illustration often prompted a reissuance of novels either in serial or volume form to satisfy the desires of the market. This is the case of the illustrated version of Lady Audley’s Secret in the London Journal, which this project takes as its subject. However, more than just catering to the wishes of its readers, the London Journal’s serialization of Braddon’s work performed a vital function in the text's development.

The Illustrated Lady Audley's Secret

Lady Audley’s Secret has a complex publication history. It first began serialization in 1891 on July sixth in the Robin Goodfellow magazine and continued in installments until September twenty-eighth when the publication folded. Only partially complete, the novel was reissued in the Sixpenny Magazine from January to December of 1862, this time serialized in its entirety. During the course of this second serialization, the novel was published in three-volume format in October of 1862 for readers who could afford to access it. The novel continued to be issued in subsequent editions, each time with various emendations, additions, and deletions until its third “revised” edition, which was used for all subsequent editions and for the novel's third serialization, this time with accompanying illustrations, in the London Journal.3 This twenty-two part, illustrated publication ran between March and August 1863 after sufficient demand from readers. Though Braddon’s story would have been well-known to those who read it in the London Journal, whether by reputation alone, its other serializations, published editions, or various theatrical adaptations which began in 1862, the text of Lady Audley’s Secret was highly variable and those who had access to the final, revised third edition would have been limited in number compared to those who experienced Braddon’s story in its first fluctuating formats. As such, the combination of both the stabilized, “final" version of this text and the illustrated content present a first encounter of sorts for the wide readership of the London Journal who would have met Lady Audley as she has appeared since the novel was stabilized.

This encounter was marked not only by its textual deviations from its original, widely-dispersed forms in its first serialized editions and printings, but for its inclusion of illustrations which were, like Leighton and Surridge describe them, “primary because…images often came first in the reading process. Victorian readers regularly saw illustrations before reading letterpress.”4 And this is particularly true of the London Journal’s Lady Audley’s Secret, which featured illustrations that formed the headings for many of its first installments with accompanying captions that would characterize and condition the reader’s contemplation of the subsequent issue. This classifying function did not regulate itself to only those images which directly related to the novel itself. In the case of serialized novels, often appearing within the pages of a periodical or magazine, these texts were equally influenced by their primary illustrations as well as the illustrations which framed and surrounded their content.

The London Journal’s serialization of Lady Audley’s Secret was run concurrently with other illustrated installments including The Woman in Black: Or Buried Alive by Gordon Smythies, The Poor Girl by Pierce Egan, and Ida Lee: Or the Child of the Wreck by Fairfax Balfour. Sometimes, these illustrated texts even share a direct, tangible connection with Lady Audley’s Secret’s illustration:

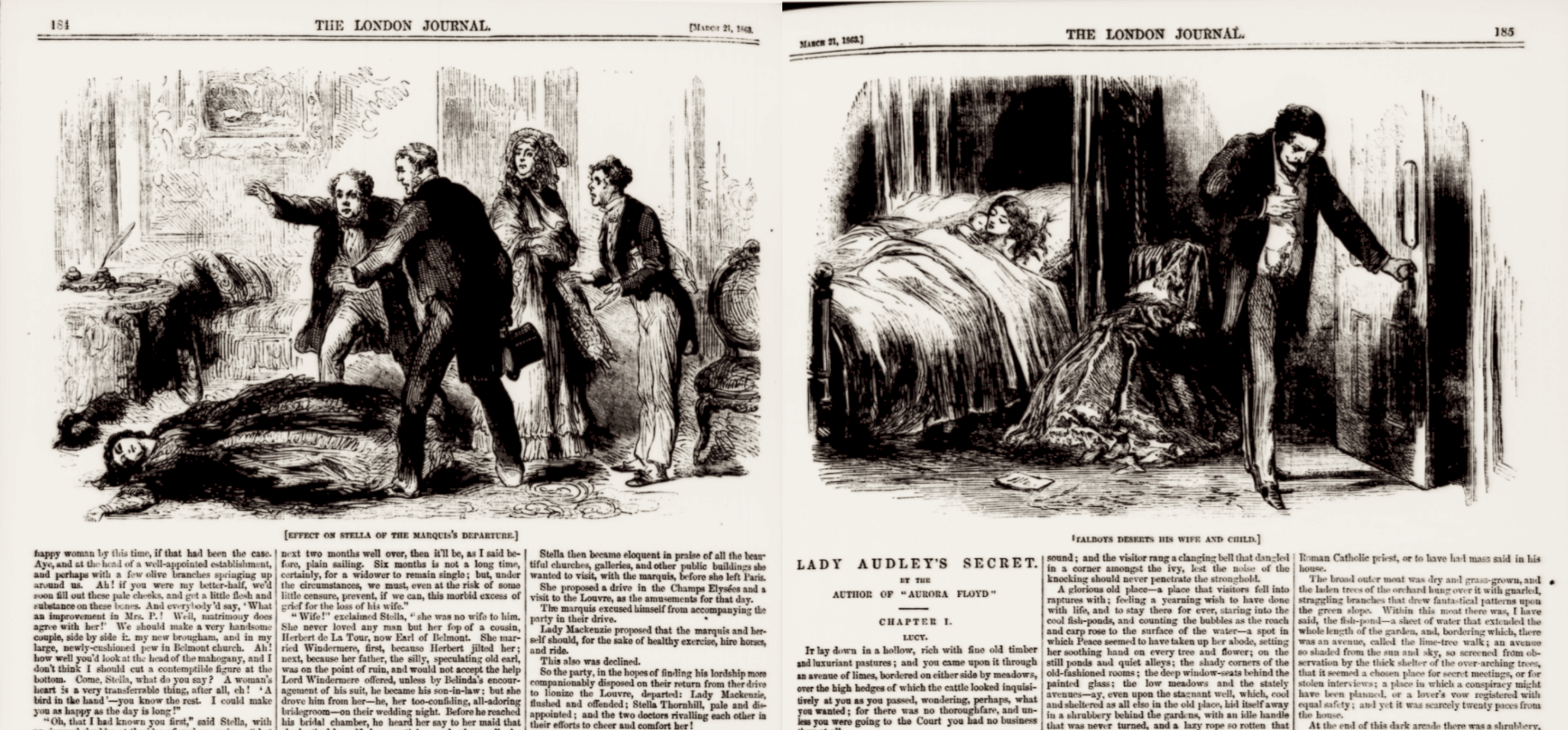

The first installment of Lady Audley’s Secret appears at the end of an installment of The Woman in Black. The two serials meet on full pages at the center of the magazine with the end of The Woman in Black on the left-hand page and the beginning of Lady Audley’s Secret on the opposing page…Each incorporates an image that covers the top third of the page above the two columns of text below. Because they face each other and are similar in size, the two images seem to speak to one another…The layout encourages readers to consider the relationship between the images.5

More than just sharing a position within the center of the London Journal, these two illustrations bare a remarkable resemblance in their contents. Both illustrations show a departure: the first, of the Marquis and the second, of George Talboys. While one shows the effects of this departure by the collapsed figure of Stella after her knowledge of the Marquis disappearance, the other shows a sleeping figure, unconscious of the fleeing Talboys who will eventually be known as Lady Audley. The juxtaposition of these two images forms something of a foreshadowing for the novel. Visually, the two images mirror each other with the female figures lying recumbent and the erect figures in motion appearing in opposite directions as if they were mirrored, but where one suggests peace and ignorance in its central character, the other reflects chaos and tragedy. Giving its readers a sense of the consequence of Talboys departure, the London Journal places these two frontispieces in contiguity as if The Woman in Black was indicative of the story to come.

The Visual Ecology of Periodicals

Mark Turner has described the nature of periodicals as “multitextual and plural” showing how the very environment of the periodical creates complex relationships between content, not only forging a spatial connection between a page’s surroundings, but a relationship of discourse, internally within the periodical itself and externally within the world of its readers.6 These connections brought about by the constitution of the periodical and its intimate relationship with the everyday have particular applications when it comes to the visuality of the periodical. For, the plurality of periodicals are not only textual, they are visual, brought about by the interaction of various illustration, both relating to fiction and non-fiction, creating a specific type of visual ecology that is made out of their various placements and associations. The term “ecology” is an apt descriptor for the type of connections it describes. Highlighting the patterns of relation among its various participants, ecology stresses the interrelation of its parts, showing how its many participants shape one another by their situational placement and correlational content. Such relationships are extant in the London Journal’s serialization of Lady Audley’s Secret whose boundaries brush up against both fiction and non-fiction, as well as various pieces of text and illustration, all which participate in the construction of reader understanding.7