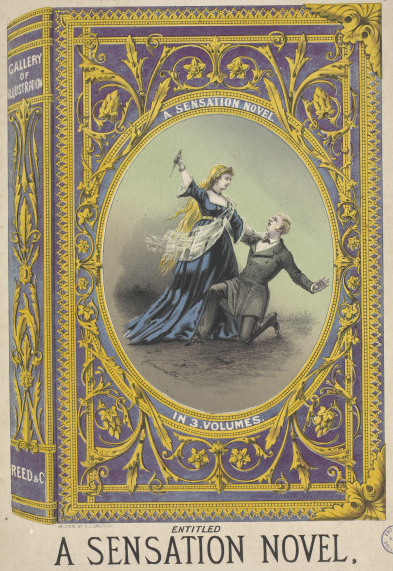

Advertising poster for a production of A Sensation Novel,

an 1871 comic musical play by W. S. Gilbert.

The 1860s was a decade marked by an infatuation of the public in all matters sensational. Permeating throughout advertisements, journalism, preaching, science, theater, art, and literature, it seemed that spectacle and scandal were preoccupations which touched every aspect of Victorian life. Perhaps best epitomized in the sensation novel, a categorization which Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret helped to form and popularize, the discourse of sensationalism extended to all manner of cultural productions and became almost omnipresent in British society. During “the 1860s and into the 1870s ‘sensation’ or ‘sensational’ were ubiquitous critical or descriptive terms”1 which delineated the emotionally violent stimulation that accompanied encounters of the sensationalist genre.

Characterized by spectacular popularity, the sensation novel grew out of and alongside these other discourses of sensation that were found in a “wide range of popular forms such as the Gothic novel, which flourished at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Newgate tales of crimes and criminals, penny magazines, broadsheet street literature, stage melodrama and sensational journalism.”2 Sensation, in this sense, was not only present in the story lines of these novels, which often featured bigamy, murder, deception, and other events of scandalous natures, but also in their popularity. Linked to wider discussions of the public’s morality and intellect, these novels participated in the age’s preoccupation with the enigma of sensation in its ability to be widely and simultaneously coveted and criticized.

The climate in which Lady Audley’s Secret would have been received was colored by this on-going discussion about the merits and malignancy of sensation. Released on the same day as the first issue of Lady Audley’s Secret in the London Journal, the “Softening of the Brain” in The Saturday Review embodies a tone common to sensation’s critique:

The present craving for ‘Sensation’ has a very ugly look. The word itself is a kind of confession of mental debility, insinuating as it does, that the powers of the mind are useless for purposes of instruction or enjoyment, and that we must fall back upon the senses. Can we have any doubt that the public brain is in a bad way, when we find that it is incapable of relishing anything that is not flavoured by this unhealthy stimulus?...it is present in everything we take up…In fiction, it has raised to the full rank and dignity of a novel the sort of tale that used to appear, adorned with hideous woodcuts, in the columns of the penny periodical…3

As with this excerpt, “[t]he sensation debate and the sensation novel itself were…the focus for a range of interrelated social tensions and anxieties… arising from contemporary social changes and the attendant challenging and questioning of the social and moral status quo.”4 The rise of sensation fiction to “the full rank and dignity of a novel” coincided with fears of other sorts of mobility and change in the institutions of the family, gender, and the social classes. Though the idea and allure of sensationalism was not wholly new during this decade, it was the sensation of sensation itself that reached new heights and imposed itself upon the cultural consciousness, leaving lasting marks upon the realms of reality and fiction—it was “the Age of Sensation.”5