Pre-Raphaelites and Print Culture

The Summer Snow by Edward Burne-Jones, 1863.

Metaphors of the visual arts are frequently employed to describe literature—a writer paints a picture, they color a scene, sketch a character, illustrate a dialogue. But, as has been noted, the print culture of the nineteenth-century placed an even greater premium on the interactions of the visual and linguistic arts as illustration became intertwined with print and commonplace in the production of the novel.1 More than just the presence of visuality alongside textuality, there were "a set of pictorial demands placed on novelists, expected not only to be masters of the art of narrative but also to be familiar with the visual arts…[and were] expected to understand painterly techniques to such an extent as to be able to employ them in their narratives or, even further, to transform pictorial into narrative techniques.”2 Such a requirement necessitated an awareness of the Pre-Raphaelite movement for novelists of the nineteenth-century based on their popularity and prominence, their predisposition to the art of the visual and the verbal, and on their prevalence in the world of print culture.

The Pre-Raphaelites were renowned painters, but they were also illustrators and worked in some of the most well-known Victorian periodicals of the day. Frequently associated with the illustration of poetic works, the Pre-Raphaelites also worked in novels. Their particular attention to the intricacies of representation, their commitment to natural and truthful portrayal of subject over idealized beauty coincided well with the nineteenth-century novel’s realism, but even for works of sensation, their principles encouraged the ability of illustration to faithfully capture and portray the emotions elicited within the text. Where novelists and their illustrators were tasked with painting a portrait of story, the Pre-Raphaelite influence extended beyond these collaborative moments and were, at times, infused into the world of the novel itself.

Portraiture in Lady Audley’s Secret

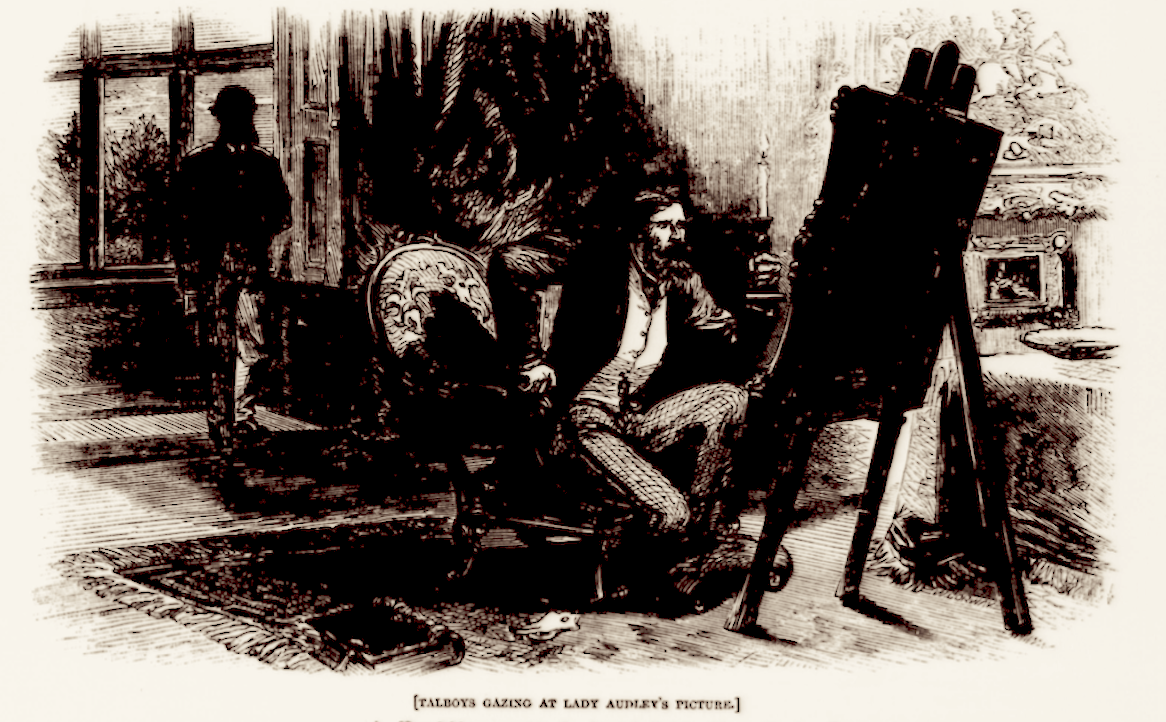

George Talboys contemplates Lady Audley's portrait.

In Lady Audley’s Secret, Robert Audley gazes upon a portrait recently commissioned of Lady Audley and remarks:

Yes; the painter must have been a pre-Raphaelite. No one but a pre-Raphaelite would have painted, hair by hair, those feathery masses of ringlets with every glimmer of gold, and every shadow of pale brown. No one but a pre-Raphaelite would have so exaggerated every attribute of that delicate face as to give a lurid lightness to the blonde complexion, and a strange, sinister light to the deep blue eyes. No one but a pre-Raphaelite could have given to that pretty pouting mouth the hard and almost wicked look it had in portrait.3

As Braddon draws this portraiture of the novel’s namesake, the reader can see this image come into view before them, and in the case of Lady Audley’s Secret’s contemporary readers, would have had a wealth of associations of Pre-Raphaelite portraiture “that they had seen in galleries or in engraved reproductions in illustrated magazines or papers”4 to help them along in their imaginative reverie. Such a description forges an intimate connection with the characterization of Lady Audley and the Pre-Raphaelite tradition. More than just grounding the reader with reference of familiarity, this invocation lays a great deal of groundwork for the development and complexity of Lady Audley’s character, the tone of the portrait suggesting that, far from an archetype of female villainy or idealism, Lady Audley will fit neither pre-defined mold.

The Pre-Raphaelites stressed the expression of “the idiosyncratic uniqueness…instead of excluding ‘particularities,’ they accurately displayed minute details—even ‘blemishes.’”5 Though Lady Audley’s painting harkens to ideals of feminine beauty in the “feathery masses of ringlets,” “the deep blue eyes,” and the “pretty pouting mouth,” there remains a strangeness in the “lurid mass of color” and the “ripe scarlet of the pouting lips.”6 Indeed, it seems “that sometimes [the] painter is in a manner inspired, and is able to see, through the normal expression of the face, another expression that is equally a part of it, though not to be perceived by common eyes.”7 Rather than suggest a binary nature of Lady Audley’s character, the indecipherable peculiarity implies an intricacy to her nature, encouraged by the “Pre-Raphaelite avant-garde gaze [which] revealed hitherto unexplored perspectives as, for instance, unconventional beauty in conventional ugliness, feminine fragility in masculinity, and masculine strength in conventional femininity.”8

-

'Bocca Baciata' by Dante Gabriel Rosetti

-

‘Il Dolce far Niente’ by Holman Hunt

‘Bocca Baciata’, by Dante Gabriel Rosetti was completed in 1859 and was likely exhibited in 1860, a year before Lady Audley’s Secret first started to appear in print. This is one candidate for an example portrait against which readers could have associated Lady Audley’s painting. Other examples include ‘Il Dolce far Niente’ by Holman Hunt, completed in 1859 as well. Holman Hunt is, incidentally, mentioned explicitly in Lady Audley’s Secret at a later point in the text:

If Mr Holman Hunt could have peeped into the pretty boudoir, I think the picture would have been photographed upon his brain to be reproduced by-and-by upon a bishop’s half-length for the glorification of the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood. My lady in that half recumbent attitude, with her elbow resting on one knee, and her perfect chin supported by her hand, the rich folds of drapery falling away in long undulating lines from the exquisite outline of her figure, and the luminous rose-coloured firelight enveloping her in a soft haze, only broken by the golden glitter of her yellow hair.9

The connotation of Lady Audley with Pre-Raphaelite portraiture in both the opening of the novel and here in its second volume, as well as the fascination attributed to the contemplation of her character, seen here in the narrator’s reflections and in the captivation her portrait renders upon George Talboys and Robert Audley, encourage the reader to carefully contemplate Lady Audley’s character. Such deliberate attention intimates that, just as we think we know her, a glimmer of the eye or a fold of the skirt may betray her intelligibility and present something new.